https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2017/03/wordstar-a-writers-word-processor/

Enlarge

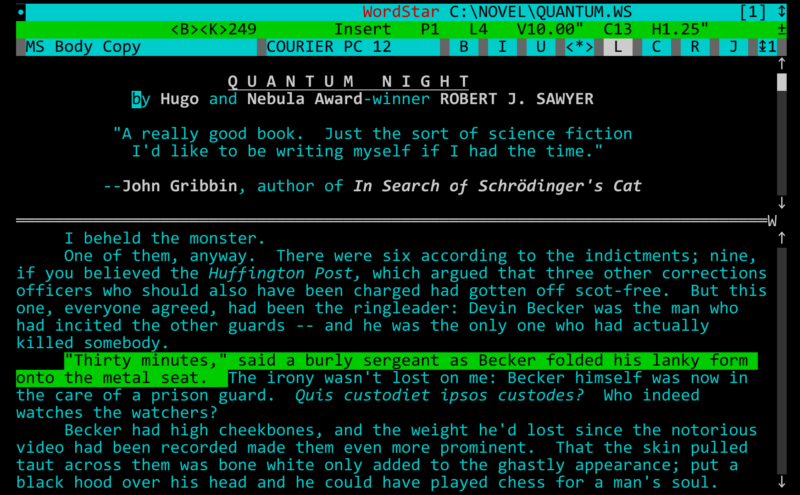

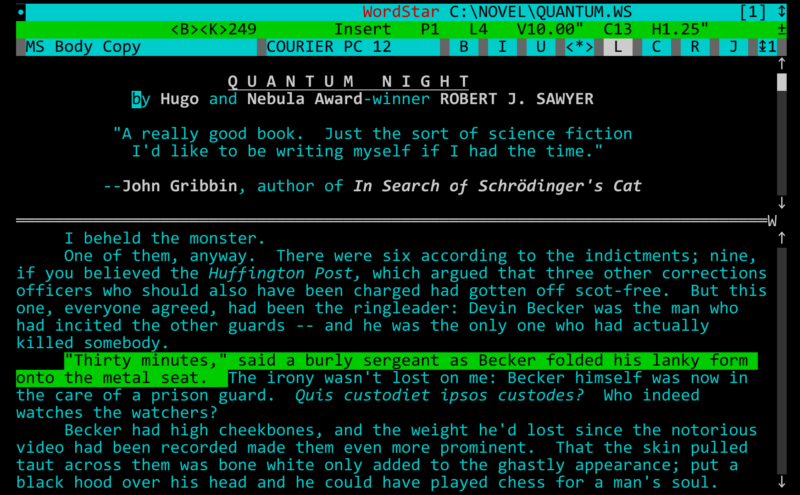

This essay was written in 1990 and updated in 1996 by Robert J. Sawyer, the sci-fi author writer behind such novels as Flashforward and more recently Quantum Night. 27 years later, he's still using WordStar.

As recently as 2014, George R. R. Martin, of A Song of Ice and Fire fame, used a DOS-based version of WordStar, and probably still does today.

I'm not sure why they don't just use Emacs or something. Enjoy this walk down memory lane...

Many science fiction writers—including myself, Roger MacBride Allen, Gerald Brandt, Jeffrey A. Carver, Arthur C. Clarke, David Gerrold, Terence M. Green, James Gunn, Matthew Hughes, Donald Kingsbury, Eric Kotani, Paul Levinson, George R. R. Martin, Vonda McIntyre, Kit Reed, Jennifer Roberson, and Edo van Belkom—continue to use WordStar for DOS as our writing tool of choice.

Still, most of us have endured years of mindless criticism of our decision, usually from WordPerfect users, and especially from WordPerfect users who have never tried anything but that program. I've used WordStar, WordPerfect, Word, MultiMate, Sprint, XyWrite, and just about every other MS-DOS and Windows word-processing package, and WordStar is by far my favorite choice for creative composition at the keyboard.

That's the key point: aiding creative composition. To understand how WordStar does that better than other programs, let me start with a little history.

WordStar was first released in 1979, before there was any standardization in computer keyboards. At that time, many keyboards lacked arrow keys for cursor movement and special function keys for issuing commands. Some even lacked such keys as Tab, Insert, Delete, Backspace, and Enter.

About all you could count on was having a standard QWERTY typewriter layout of alphanumeric keys and a Control key. The Control key is a specialized shift key. When depressed simultaneously with an alphabetic key, it causes the keyboard to generate a specific command instruction, rather than the letter. The control codes are named Ctrl-A through Ctrl-Z (there are a few punctuation keys that can generate control codes, too). Control codes are frequently indicated in text by preceding the letter with a caret, like so: ^A.

WordStar's original designers, Seymour Rubenstein and Rob Barnaby, selected five control codes to be prefixes for bringing up additional menus of functions: ^O for On-screen functions; ^Q for Quick cursor functions; ^P for Print functions; ^K for block and file functions; and ^J for help.

Now, the first three of these are alphabetically mnemonic. The last two, ^K and ^J, might at first glance seem to be arbitrary choices. They aren't. Look at a typewriter keyboard. You'll see that for a touch typist, the two strongest fingers of the right hand rest over ^J and ^K on the home typing row. WordStar recognizes that the most-often-used functions should be the easiest to physically execute.

To serve as arrow keys for moving the cursor up, left, right, or down, WordStar adopted ^E, ^S, ^D, and ^X. Again, looking at a typewriter keyboard makes the logic of this plain. These four keys are arranged in a diamond under the left hand:

Such positional, as opposed to alphabetic, mnemonics form a large part of the WordStar interface. Additional cursor-movement commands are clustered around the E/S/D/X diamond:

^A and ^F, on the home typing row, move the cursor left and right by words. ^W and ^Z, to the left of the cursor-up and cursor-down commands, scroll the screen up and down by single lines. ^R and ^C, to the right of the cursor-up and cursor-down commands, scroll the screen up and down a page at a time (a "page" in the computer sense of a full screen of text).